Text adapted from Eye of the Bird: Visions and Views of D.C.’s Past (gallery guide, 2018), produced by The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum.

The world seen from above has always held great interest for the public. Perhaps it is the envy of birds, but in many cultures, examples of bird’s eye views exist from ancient times right up to the current popularity of Google Earth and drones.

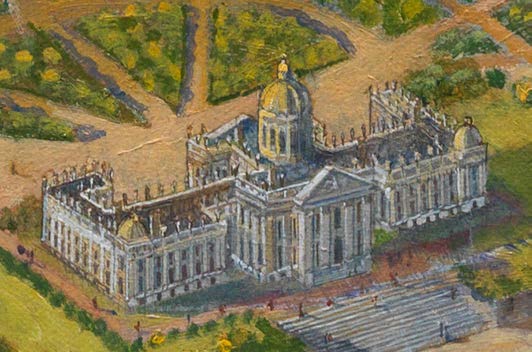

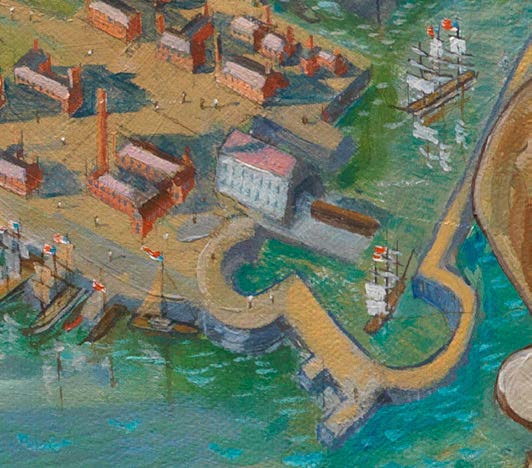

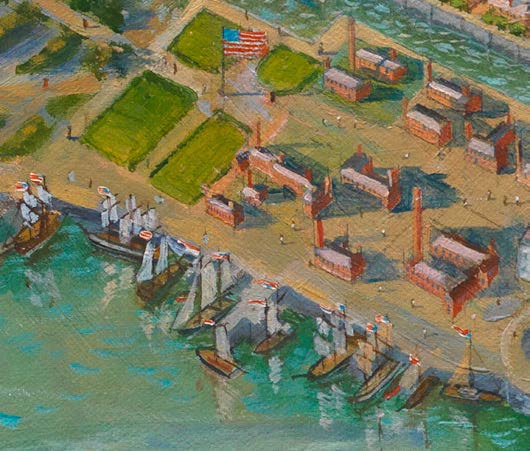

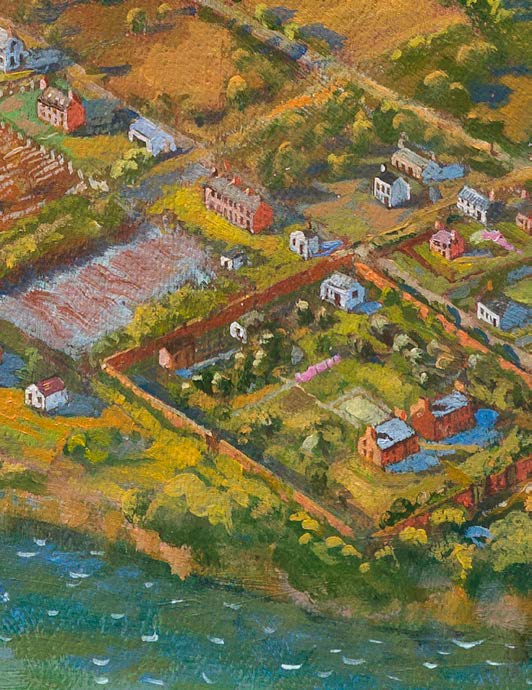

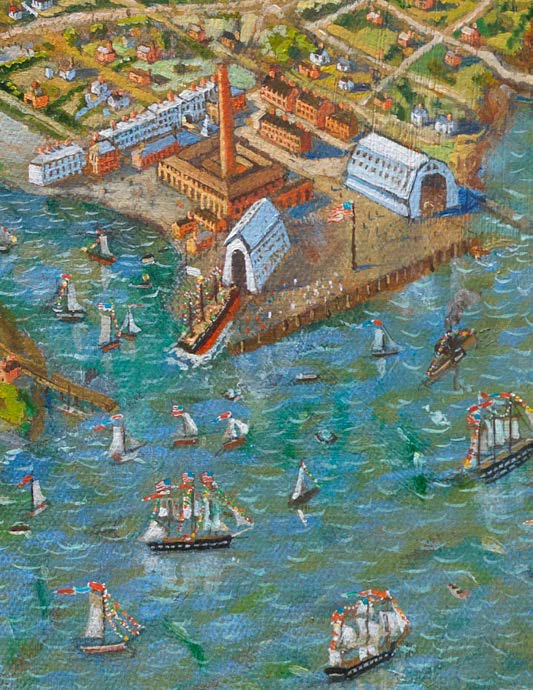

Eye of the Bird: Visions and Views of D.C.’s Past introduces two new bird’s eye view paintings of Washington, D.C. by Peter Waddell. The Indispensable Plan illustrates for the first time city planner Peter (Pierre) L’Enfant’s 1791 vision for the city. The second painting, The Village Monumental, reveals how D.C. had actually developed by the time of L’Enfant’s death in 1825.

Using historical prints of city views that were originally drawn by hand, Eye of the Bird also shows how the bird’s eye view genre and the city of Washington, D.C., both evolved in the 19th century and examines the process by which they were created.

The Indispensable Plan

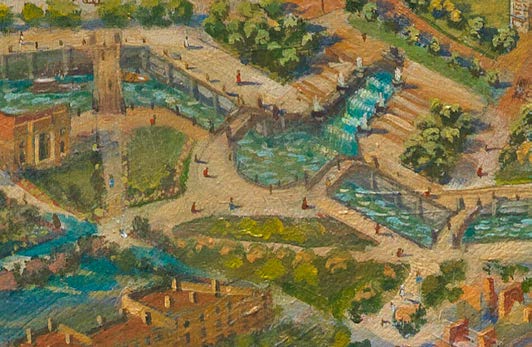

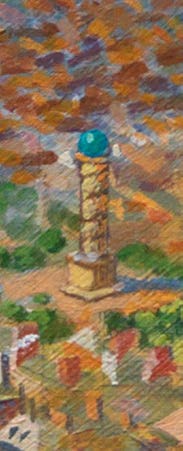

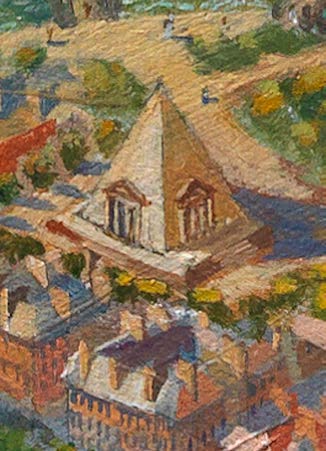

L’Enfant planned for every conceivable need, from canals to carry people and goods through the city to the public spaces, government buildings, and military installations. He even came up with a strategy to distribute the city’s growth, by setting aside circles where each state could establish a presence.

The Village Monumental

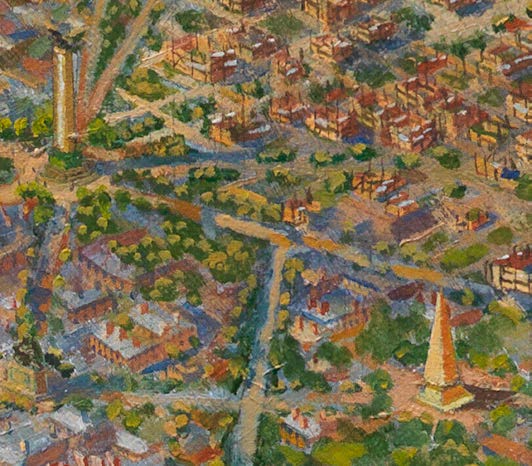

But things didn’t go according to plan. By L’Enfant’s death in 1825, the city had progressed much more slowly than initially hoped. Limited funds from Congress and unrealized profits from the sales of city lots were not enough to build L’Enfant’s ideal city. Rampant land speculation further hampered development.

The canal, the economic and geographic center of L’Enfant’s city, was unfinished. The park connecting the White House and the Capitol was being used by farmers. L’Enfant’s plans for a national university, a bevy of fountains, and avenues of elegant, stone and brick buildings seemed like a dream.

Instead, neighborhoods popped up around the city as scattered villages. The picturesque public spaces L’Enfant had theorized were nowhere to be seen.

Much of Washington was still agrarian in 1825. Farmers utilized unclaimed land, including the future National Mall, for growing crops and grazing animals.

“I had the urge to create paintings about Washington, D.C.’s conception and earliest years—it seems a magical thing to recreate a world long gone or never built. I wanted to paint the whole city as President George Washington and designer Peter L’Enfant envisioned it, and then paint what had actually happened here by 1825 when L’Enfant died. I am grateful to my patron, Albert H. Small, and the George Washington University Museum for the opportunity to bring my vision to fruition.”

Peter Waddell, 2018